See the entire The Fantastic Machine series →

“A bad system will beat a good person every time.”

—W. Edwards Deming

Welcome back to the control room. So far in your training, you have toured the entire physical grid. You have seen how power is born in massive generators, how it travels across the country on high-voltage transmission lines, and how it makes the final, intricate journey to your customer’s doorstep through the distribution system. You now have a map of the physical machine.

But a machine of this scale does not run itself. It is governed by a complex, invisible structure of rules, authority, and economics. You’ve seen the physics in action. Now it is time to learn the politics and the marketplace. In this session, we are zooming out from the poles and wires to see the big picture. You will learn about the organizations that make the rules, who has the ultimate authority during an emergency, and how the price of the electricity you deliver is set every five minutes in a high-stakes auction. This is the story of how the grid is managed.

The Grid’s Management Structure

To understand how you fit into the grand scheme of things, you need to see the grid’s management from two different angles; the hierarchy that ensures physical reliability and the governance that ensures market integrity.

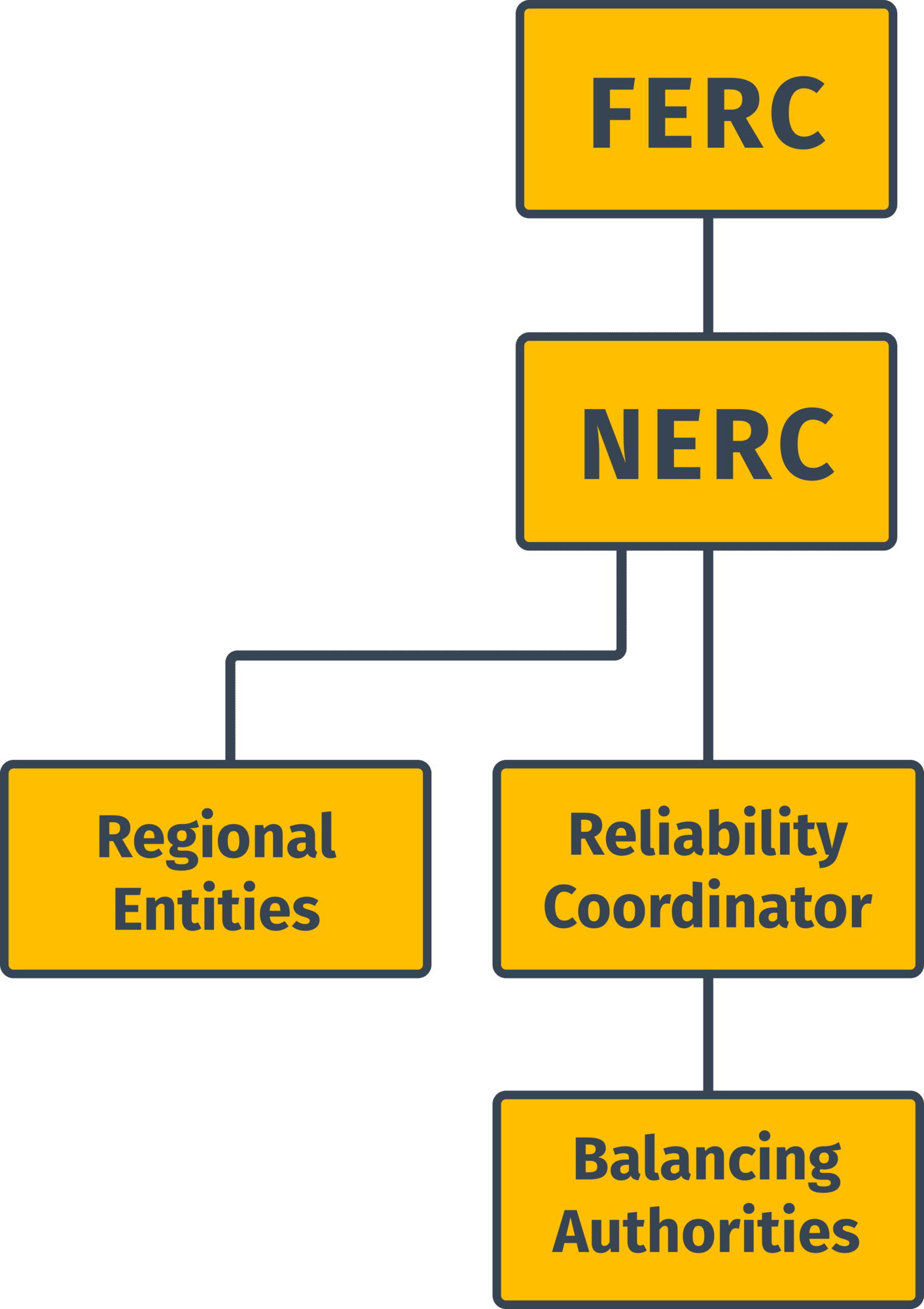

The Reliability Hierarchy – Your Chain of Command

When a crisis is unfolding, there is no ambiguity about who has the authority to act. You are part of a strict, top-down chain of command focused on one thing: keeping the lights on.

- NERC (North American Electric Reliability Corporation): At the very top of the pyramid is NERC. Think of them as the lawmakers. NERC is certified by the federal government to write and enforce the mandatory reliability standards that everyone on the bulk power system, including you, must follow. They create the rulebook you will live by.

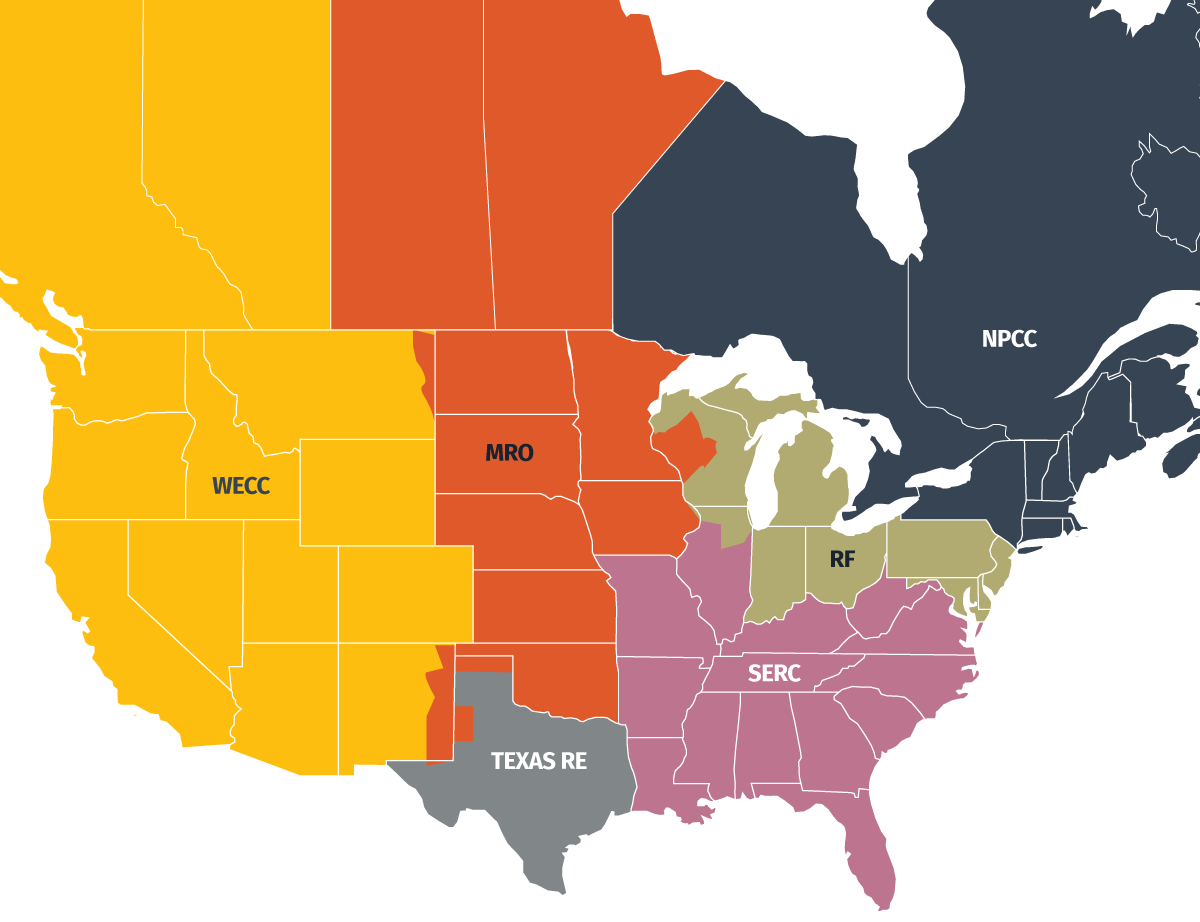

- Regional Entities: NERC delegates enforcement to several Regional Entities. These organizations (like WECC in the West, SERC in the Southeast, or MRO in the Midwest) are not just auditors. They are the primary regional experts. They perform their own independent reliability assessments and seasonal forecasts, identifying the specific risks for their part of the continent, such as drought and wildfire risks in the West or hurricane threats in the Southeast.

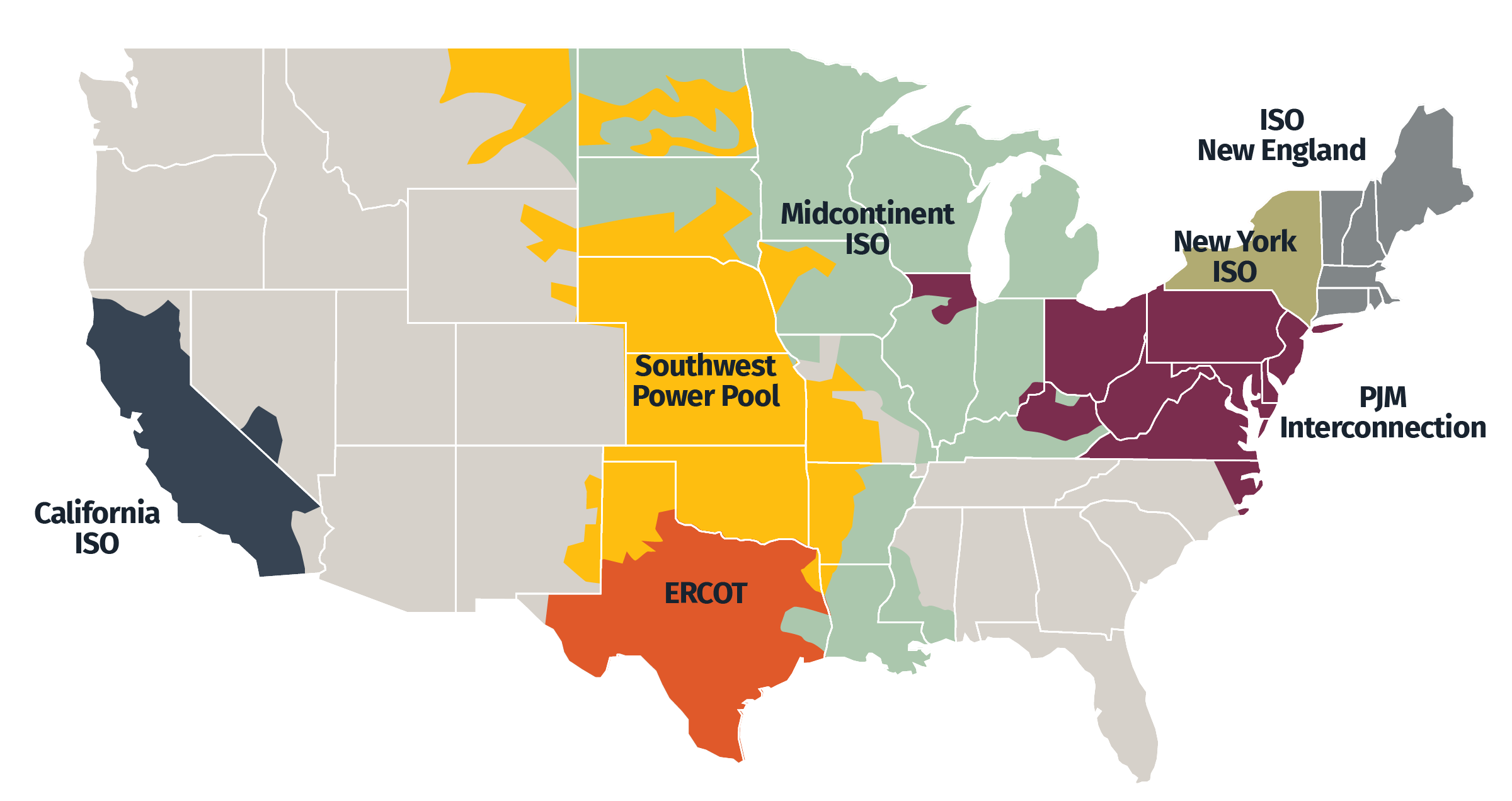

- Reliability Coordinators (RCs): These are your air traffic controllers. The RC is the entity with the ultimate real-time authority over your wide area. The large grid operators you may have heard of, like PJM, MISO, and the California ISO (CAISO), all serve as the RC for their region. Their job is to maintain a top-down view of the entire system. In an emergency, the RC has the ultimate authority to direct any action necessary to maintain reliability, from starting a generator to dropping load. Your compliance with their orders is mandatory.

- Balancing Authorities (BAs) and Transmission Operators (TOPs): This is where the regional plan meets the physical reality of the grid, and it’s where you work. The Balancing Authority (which in an RTO like PJM is the RTO itself, while in non-market areas it’s a utility like Duke Energy) is responsible for the second-by-second balancing of load and generation. As a Transmission Operator (TOP) for a utility like Dominion Energy or AEP, you are responsible for the real-time operation of the transmission system. You monitor the system, execute switching, and ensure the physical flows on the grid stay within safe limits. While you are at the forefront of real-time operations, strategic decisions about infrastructure upgrades are a collaborative effort. The Transmission Owner (TO), which owns the physical assets, and the Transmission Planner are primarily responsible for long-term strategy and planning for new facilities. As a TOP, your intimate knowledge of the system’s real-time behavior provides critical operational input into their planning process, ensuring that the grid of tomorrow is designed to be operated reliably and efficiently.

Operator Briefing: NERC vs. FERC and an International Grid

It is easy to confuse NERC and FERC, but for you as an operator, the distinction is critical. Think of it this way: NERC is about reliability and the laws of physics. They write the technical standards you must follow to keep the grid stable. FERC is about economics and the laws of commerce. They regulate the wholesale markets and the financial side of the business.

It’s also crucial to remember that NERC’s authority isn’t limited to the United States. The “North American” in their name is literal. The grid you manage is an international machine, and NERC’s standards are mandatory across most of Canada and a portion of Baja California, Mexico. This international cooperation is essential. For example, the United States is a net importer of electricity, with the vast majority of those imports coming from clean hydroelectric power in Canada. This requires a common set of reliability rules that everyone on both sides of the border agrees to follow.

This entire hierarchy provides the operational structure for implementing and enforcing a detailed, technical rulebook. The NERC reliability standards are a library of hundreds of individual requirements that govern every aspect of your job. They include:

- FAC (Facilities): These standards govern the physical equipment. They cover everything from the technical requirements for connecting a new facility to the grid, to the critical need for vegetation management (FAC-003), the constant battle we explored on the distribution system in Part 4. Most importantly, they include the rules for establishing the safe operating limits, or Facility Ratings, that you must never violate.

- O&P (Operations & Planning): This is the largest group of standards, and it directly governs your actions. It includes the rules for how you must communicate with other control rooms (IRO standards), the specific instructions for managing your equipment (TOP standards), and the protocols for matching generation to load second-by-second (BAL standards).

- PRC (Protection and Control): These standards are focused on the grid’s automated immune system. They set the requirements for the protective relays that you will see in action, detecting faults and automatically isolating them in fractions of a second, putting the principles of protection coordination you learned about in Part 4 into practice.

- EOP (Emergency Operations Planning): This is your emergency playbook. These standards require your utility to have a detailed, tested plan for how you will restore the grid after a major blackout (a “blackstart” plan) and how you will shed load in a controlled way to prevent a system collapse.

- CIP (Critical Infrastructure Protection): This is one of the most significant and complex sets of standards, focused entirely on security. The CIP standards mandate the strict, auditable controls you must follow to protect the grid from both cyber and physical threats.

- MOD (Modeling, Data, and Analysis): The advanced tools on your console, from the real-time contingency analysis to the long-term planning studies, all depend on having an accurate computer model of the grid. Think of this as a “digital twin” of the physical system. The MOD standards ensure that this model is a faithful representation of reality. They require your organization to have formal processes for collecting and validating all the necessary data, from the physical characteristics of a transmission line down to the specific settings of a protective relay, and for sharing that model data with the other entities in your interconnection.

- PER (Personnel Performance, Training, and Qualifications): You can’t be in this chair without meeting these standards. The PER standards ensure that you and every other system operator undergo rigorous training and certification to prove you have the knowledge and skills required to manage the bulk electric system reliably.

This entire reliability framework is built on a foundation of clear authority and proven engineering. Its rigid and hierarchical structure is a direct response to the laws of physics, which demand precision and leave no room for ambiguity. This stands in stark contrast to the other side of the management coin, which is the governance of the competitive electricity markets you will participate in.

Market Governance – Keeping it Fair and Independent

While the reliability hierarchy is rigid and top-down, the governance of the competitive markets is a different beast entirely. It is a carefully constructed ecosystem designed to be independent, transparent, and collaborative. This structure is essential for building the trust required for hundreds of competing companies to participate in a single, unified system.

- The Independent Operator (ISO/RTO): The ISO or RTO you work for is a unique entity, created with a primary mission to ensure the reliability of the bulk power system across a wide region. To achieve this, they also operate the competitive wholesale electricity markets. They are non-profit, independent organizations designed to be impartial. To guarantee this impartiality, their governance is typically split into two parts. First, an independent Board of Directors, whose members are explicitly prohibited from having any financial stake in a market participant, provides ultimate oversight. Second, a formal stakeholder process allows members (a diverse group including utilities, power plant owners, and consumer advocates) to openly debate and vote on proposed changes to the market rules you operate under.

- The Market Monitor (The Watchdog): Every fair market needs a referee. Your ISO has an Independent Market Monitor (IMM), an independent entity that acts as a watchdog. A great example is Monitoring Analytics, which serves as the IMM for PJM. The IMM’s job is to constantly analyze market data to detect and deter any participant from exercising market power, for example, a large generator withholding its output to artificially drive up prices. The IMM reports its findings publicly, acting as a crucial, transparent check and balance on the market’s integrity.

- Managing the Seams (Where Grids Meet): A fascinating management challenge you will encounter exists at the borders, or “seams,” between different ISOs. Because each ISO has slightly different market rules, these boundaries can create operational and economic inefficiencies. To manage this, your ISO has Joint Operating Agreements (JOAs) with its neighbors to better coordinate everything from power dispatch to transmission planning across your borders.

- Life Outside the Market (Non-ISO/RTO Areas): It’s important for you to remember that this market-based structure only covers about two-thirds of the United States. In large parts of the Southeast and the West, the grid is still managed by traditional, vertically integrated utilities. These utilities own their own power plants, transmission lines, and local distribution system. In these regions, there is no competitive wholesale market. The central planning tool is the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), a long-term blueprint that must be approved by the state Public Utility Commission and dictates what the utility will build. While many utilities within RTOs are also required by their states to produce IRPs, their function is different; they act as a strategic forecast that informs the utility’s participation in the RTO’s regional planning and market processes, rather than being the ultimate decision-making tool.

Operator Briefing: The Ghost of Enron

The role of the Market Monitor is so critical because of the lessons you must learn from the California electricity crisis of 2000-2001. During this period, energy trading companies, most famously Enron, exploited flaws in California’s newly designed market to create artificial shortages and manipulate prices. Traders used a variety of schemes with cynical names like “Death Star” and “Fat Boy” to game the system.

For example, they would intentionally schedule more power than a transmission line could handle to create congestion, and then get paid to “relieve” that same congestion. These actions, which were legal under the flawed market rules at the time, led to rolling blackouts and cost the state billions of dollars. The Enron scandal is the ultimate cautionary tale, and it’s the reason why every modern market has an independent watchdog looking over your shoulder.

Your role as an operator is defined by the interplay between these two powerful structures: the rigid hierarchy that ensures physical reliability and the collaborative governance that keeps the markets fair. They are the human systems that control the physical and financial machine. With this framework in place, you are now ready to explore the financial engine that this structure enables.

The Financial Engine of the Grid

The flow of electrons across the grid is enabled by an equally complex flow of money. The markets you participate in are the engine that funds the entire operation, from generator fuel costs to new transmission lines. This engine is composed of several key markets, all working together.

The Energy Markets – Day-Ahead and Real-Time

At the heart of the engine is the energy market, a two-stage auction process designed to find the cheapest way to meet demand at every moment.

First is the Day-Ahead Market. The day before, generator owners submit bids to your ISO, stating how much electricity they can produce and the minimum price they are willing to accept. The ISO takes all these bids and creates a “bid stack,” ordering them from the cheapest resource to the most expensive in a process known as merit order dispatch. Based on the next day’s load forecast, the ISO then performs the critical process of unit commitment. This is where it decides which power plants (“units”) need to be turned on and scheduled (“committed”) to run. This is essential because many large generators, like the coal and nuclear plants you learned about in Part 2, can take many hours to start up. Once the units are committed, the ISO “clears” the market, and the price paid to all the selected generators is the price of the most expensive one needed, known as the clearing price.

Second is the Real-Time Market. Because the forecast is never perfect, this same auction process happens again every five minutes to adjust for real-time changes in demand and supply, allowing you to dispatch power from the pool of already-committed generators. This constant auction ensures that you are always dispatching power in the most economic way possible.

Financial Settlement – Following the Money

Once the power flows, your ISO acts as the central counterparty for the entire market, performing a massive financial settlement every day. It calculates how much energy was produced by every generator and consumed by every utility at thousands of locations, each with its own unique Locational Marginal Price (LMP). The ISO then collects money from the buyers and pays the sellers, ensuring everyone is compensated accurately.

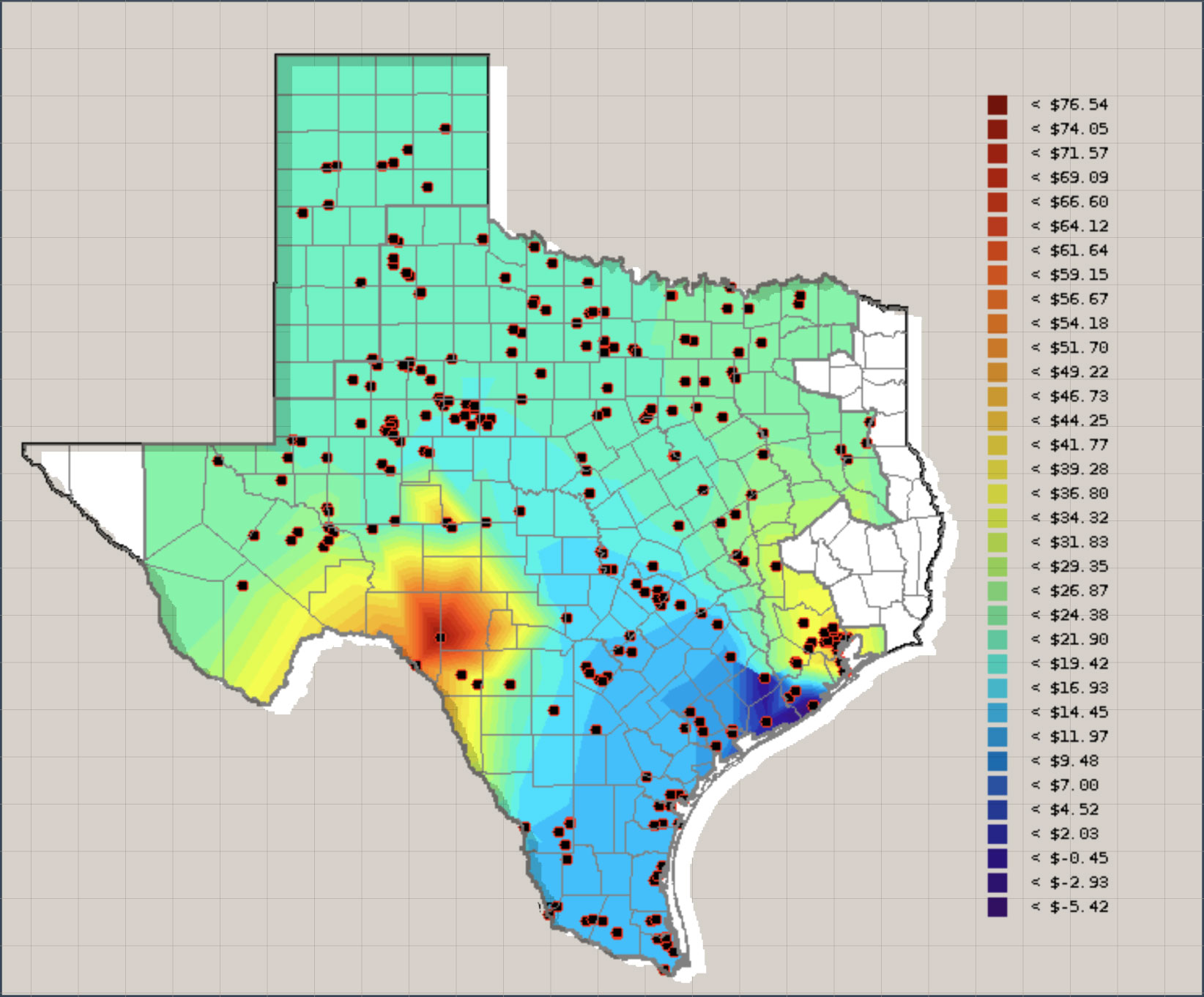

Operator Briefing: What is Locational Marginal Pricing (LMP)?

Locational Marginal Pricing (LMP) is the price of electricity at a specific point on the grid. It’s not the same everywhere, and for you as an operator, understanding why is critical. The price you see on your screen for a specific location is actually made up of three distinct parts:

- The Energy Component: This is the base cost of generating the power, determined by the bid of the most expensive power plant needed to meet demand system-wide.

- The Congestion Component: This is the cost of traffic jams on the grid. If a cheap generator can’t get its power to a city because of a congested transmission line, you have to turn on a more expensive local generator instead. The difference in price is the congestion cost, and it gets added to the LMP in that congested area.

- The Loss Component: As you know from Part 1, you lose some energy as heat when you move it over long distances. This component accounts for the cost of generating that extra “lost” electricity. The LMP is the sum of these three parts, and it’s the true cost of delivering the next megawatt of power to a specific location.

If you’re interested to know more, we have a blog post on the topic of Production Cost Analysis.

Resource Adequacy and Capacity Markets

This financial system looks beyond just today’s energy to address the fundamental requirement of Resource Adequacy, which is the need to have sufficient generation resources available to meet the projected peak electricity demand plus a safety buffer, or reserve margin. To achieve this, many ISOs run capacity markets. This market is designed to solve the “missing money” problem for generators that are needed for reliability but may not run often enough in the energy market to cover their fixed costs.

In this “forward” auction, typically held three years before the energy is needed, a developer can bid a proposed new power plant. If their bid is selected, they secure a guaranteed, multi-year revenue stream before they even break ground, which provides the financial certainty needed to obtain financing for construction. When the auction results in high prices, as has been the case recently in PJM, it’s a powerful signal that the system needs more resources, which in turn should incentivize more generation to be built. A generator that “clears” this auction receives a steady capacity payment in exchange for the obligation to be available to run during that future year. If they fail to perform when you call upon them, they face significant financial penalties.

Operator Briefing: Two Philosophies, Capacity vs. Energy-Only Markets

Not all markets you might work in are designed the same way. Most markets in the Northeast and Midwest use a capacity market to ensure long-term reliability. This approach provides a separate, stable payment to generators for being available, which is intended to encourage investment.

ERCOT (Texas), however, is a famous example of an “energy-only” market. It does not have a capacity market. Instead, it relies on the principle of scarcity pricing. During times of extreme grid stress, ERCOT allows the price of energy to rise to incredibly high levels, sometimes thousands of dollars per megawatt-hour. The theory is that the potential to earn these massive profits during just a few critical hours a year is the financial signal that incentivizes companies to build new power plants. It’s a fundamentally different, higher-risk, higher-reward philosophy for managing the grid.

This high-risk, high-reward philosophy was put to the ultimate test during the winter storm of February 2021. Widespread failures of natural gas plants and other generators led to a massive supply shortage, and prices across Texas shot up to the market cap of $9,000 per megawatt-hour for days. Because some retail electric providers in Texas offer plans that pass these wholesale prices directly to customers, some individuals received shocking electricity bills for thousands of dollars. The event was a stark illustration of the risks inherent in an energy-only market, both for generators who rely on rare scarcity events to be profitable, and for consumers who can be exposed to extreme price volatility.

Ancillary Services – The Grid’s Support System

Finally, in addition to the energy and capacity markets, your ISO also procures a suite of ancillary services. These are the essential reliability services you need to keep the grid stable second-by-second. The ISO’s software “co-optimizes” them, procuring the lowest-cost combination of energy and services simultaneously.

Operator Briefing: The First Ancillary Service

The sophisticated, multi-million dollar ancillary service markets you see today all evolved from a simple, manual task. In the earliest days of the grid, the very first “ancillary service” was manual frequency control. An operator would literally stand at a control board and watch a frequency meter. If the needle dipped below 60 Hz, they would call another power plant and tell them to produce more. If it rose above, they’d tell them to back off. Every automated signal you send and every market price you see is a modern evolution of that fundamental responsibility.

The main products you will see procured are:

- Frequency Regulation: This is a premium service provided by resources that can respond automatically to your signals, adjusting their output up and down multiple times a minute to manage the tiny deviations from the grid’s 60 Hz heartbeat.

- Operating Reserves: This is your insurance policy. Spinning reserves are generators that are already synchronized to the grid and can ramp up to full power in ten minutes or less. Non-spinning reserves are offline generators that can be started and synchronized to the grid just as quickly. You pay both to be on standby, ready to deploy instantly if another power plant suddenly fails. This is often provided by the fast-acting dispatchable generators you met in Part 2.

- Voltage Support: This is the compensation for reactive power, the “foam in the beer” from Part 1. The way this is procured varies by region. While some ISOs, like CAISO, include it in their ancillary service market, others, like PJM, compensate generators for their reactive capability through a cost-based payment defined in their tariff.

The “Virtual Power Plant” – Demand Response

For your entire career, the main tool for balancing the grid has been on the supply side; you tell a generator to produce more. But now, you have a powerful tool on the demand side. Demand Response (DR) is the concept of paying electricity customers to reduce their consumption during times of high demand or grid stress.

This isn’t just a voluntary “please conserve” message. In your RTO, DR is a formal resource. A large industrial plant, or an aggregator of thousands of smart home thermostats, can “bid” their load reduction into the markets just like a power plant. For you as an operator, a megawatt of load that is “interrupted” is just as valuable as a megawatt of generation that is “started.” This “virtual power plant” provides a critical, fast-acting tool for balancing the system and can compete directly in the Energy, Capacity, and Ancillary Services markets, often at a lower cost than a traditional generator.

This complete suite of markets for energy, capacity, and ancillary services forms the financial engine of the grid. But it does not operate in a vacuum. It is built upon a foundation of legal and regulatory oversight.

The Regulatory Rulebook

The entire market and reliability framework you operate within is overseen by a dense web of rules set by both federal and state governments.

FERC Orders – The Engine of Change

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is the ultimate economic regulator of the interstate grid. While its authority is broad, covering things like natural gas pipelines and hydroelectric dam licensing, its most critical role for you is its jurisdiction over the wholesale electricity markets. FERC doesn’t just approve the rules; it actively shapes them through FERC Orders.

A FERC Order is a legally binding ruling that can establish new market rules, approve or deny a proposed project, or direct the industry to solve an emerging problem. These orders are the result of a long, formal process. It often begins with FERC issuing a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR), which lays out a potential new rule and asks for public comment. After a lengthy period of feedback from utilities, RTOs, consumer advocates, and other stakeholders, FERC issues a final order that becomes the law of the land.

From FERC Order to NERC Standard

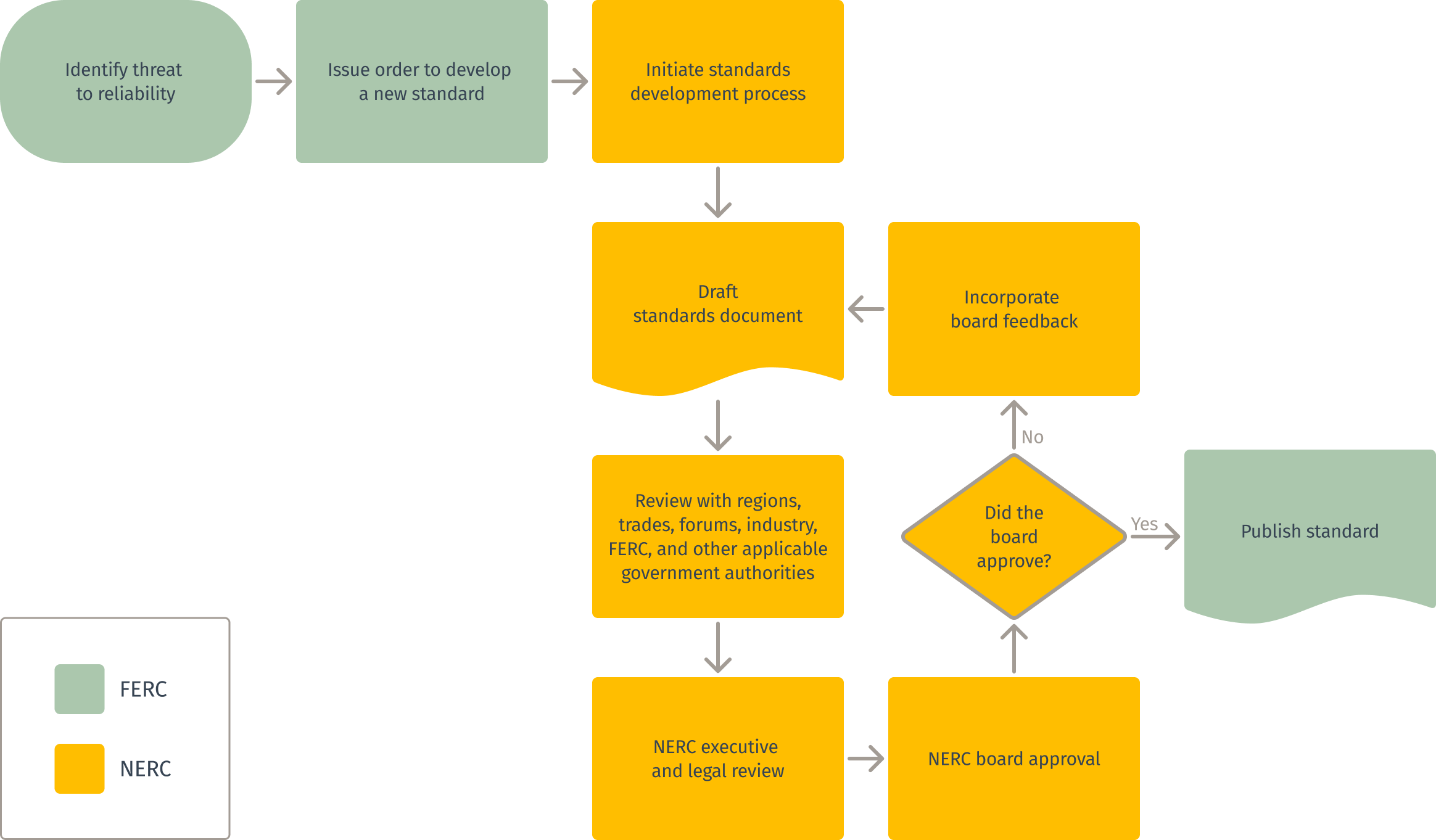

The relationship between FERC and NERC is a perfect example of this process in action. FERC has the legal authority, but NERC has the technical expertise. When FERC identifies a new threat to reliability, it will often issue an order directing NERC to develop a new, mandatory reliability standard to address it. NERC then initiates its own open, stakeholder-driven process to draft, ballot, and approve the technical details of the new standard. Once complete, the standard is sent back to FERC for final approval, at which point it becomes a mandatory, auditable rule that you must follow.

Operator Briefing: Landmark FERC Orders

To give you a sense of their power, here are a few landmark FERC orders that have fundamentally shaped the grid you operate today:

- FERC Orders 888 & 889 (1996): As you’ve learned, these are the “big bang” of competition. They required utilities to provide open, non-discriminatory access to their transmission lines, creating the competitive wholesale markets.

- FERC Order 2000 (1999): This order encouraged the voluntary formation of the RTOs and ISOs that manage the markets and the grid today.

- FERC Order 841 (2018): This order was a game-changer for energy storage. It required market operators to create rules that recognized the unique ability of batteries to both charge from and discharge to the grid, opening the door for them to compete in all the wholesale markets.

- FERC Order 2222 (2020): This groundbreaking order is aimed at the future. It requires RTOs to create rules that allow aggregations of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), like rooftop solar and home batteries, to participate in the wholesale markets, just like a traditional power plant.

- FERC Order 2023 (2023): This recent, major order is designed to fix the long backlog of new power plants waiting to connect to the grid. It overhauls the generator interconnection process, moving from a “first-come, first-served” approach to a “first-ready, first-served” model that studies projects in clusters and requires developers to meet stricter financial milestones.

State PUCs – The Local Authority

While FERC governs the interstate “superhighways,” the power to regulate the “local roads” and the final connection to the customer belongs to the states. For you as an operator, your state’s Public Utility Commission (PUC) is an incredibly powerful body.

The PUC’s authority is built on the foundational “regulatory compact.” This is the classic bargain at the heart of the utility industry: in exchange for an exclusive monopoly to serve a specific territory, your company takes on a legal “obligation to serve” every customer in that area. In return, the PUC guarantees your company the opportunity to recover its prudently-incurred costs and earn a “fair, just, and reasonable” rate of return on its investments.

You will see this in action in several key areas:

- The Rate Case: This is where that compact is put into practice. A rate case is a formal, legal proceeding where your utility must go before the PUC to justify its expenses and request any change in the retail price of electricity. Your company’s planners and engineers will present detailed evidence of their costs, from new transmission lines to vegetation management programs, and will be cross-examined by “intervenors” like the state’s consumer advocate, environmental groups, and large industrial customers.

- Siting and Permitting: This is perhaps the PUC’s most visible power. Your organization cannot build a new transmission line or power plant without first getting a “certificate of need” from the PUC. This siting process involves extensive public hearings and environmental studies and is often the single biggest hurdle to getting new infrastructure built, as it balances the regional need for a project against local opposition.

- Varying Roles: The PUC’s exact role depends on your state’s market structure. In a traditionally regulated state, the PUC oversees everything, from the cost of fuel for power plants to the price on a customer’s bill. In a “retail choice” state (like Texas or Illinois), the PUC no longer regulates the price of energy (which is set by the competitive market), but it still has critical oversight of the local utility’s “wires” (your transmission and distribution system) and must approve all the spending and rates for delivering that power.

This completes your tour of the grid’s legal and regulatory landscape. From the federal authority of FERC, which shapes the markets, to the technical mandates of NERC, which ensure reliability, and down to the state-level oversight of PUCs, which protect local customers, this entire framework provides the foundation for the complex structures you’ve learned about. It’s the set of rules that governs both the reliability hierarchy and the financial engine of the grid.

Conclusion – The Invisible Scaffolding

And that completes your tour of the grid’s management structure. You’ve seen that the physical machine is controlled by a complex human one, with two distinct sides. On one side is the rigid, top-down hierarchy of reliability, a chain of command you must follow to keep the system stable. On the other is the collaborative governance of the competitive markets you participate in, designed to keep the system efficient and fair.

You’ve learned how the flow of electrons is directed by an equally powerful flow of money through a suite of markets for energy, capacity, and the ancillary services that act as your support system. And you now understand that your every action is bound by a dense rulebook, from the high-level authority of FERC down to the detailed engineering standards of NERC.

These interlocking systems of reliability, markets, and regulation form the invisible scaffolding that supports the entire grid’s operation today. But this near-perfect reliability is not an accident, and the grid of tomorrow won’t build itself. It is the result of a continuous and disciplined planning process.

Now that you understand the management framework, it’s time to learn how it evolves. In the next session, we’ll explore the world of long-term grid planning. You’ll learn about the different time scales planners work on, from decades in the future to the next few minutes, and the engineering principles they use to design a grid that is not only efficient but can withstand the loss of its most critical components.

See the entire The Fantastic Machine series →

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.