In my previous post, I built from the ground up a case for why software engineers should use decision-driven documentation: writing docs not to capture what we’ve done, but what we’ve decided. This approach has several advantages. It:

- Captures our intent,

- Captures the software at a point in time and in a certain context,

- Contrasts the decision to other possible outcomes, and

- Helps us know when to create other docs.

The biggest challenge of this approach, however, is knowing which decisions to document. This is especially difficult because making software is decisions all the way down. We decide on what to make, when and how to make it, and who makes it. There are decisions that cover the entire project, and decisions so small we call them “nits” —louse eggs. We’re confronted with so many decisions in software development that documenting them is itself a decision.

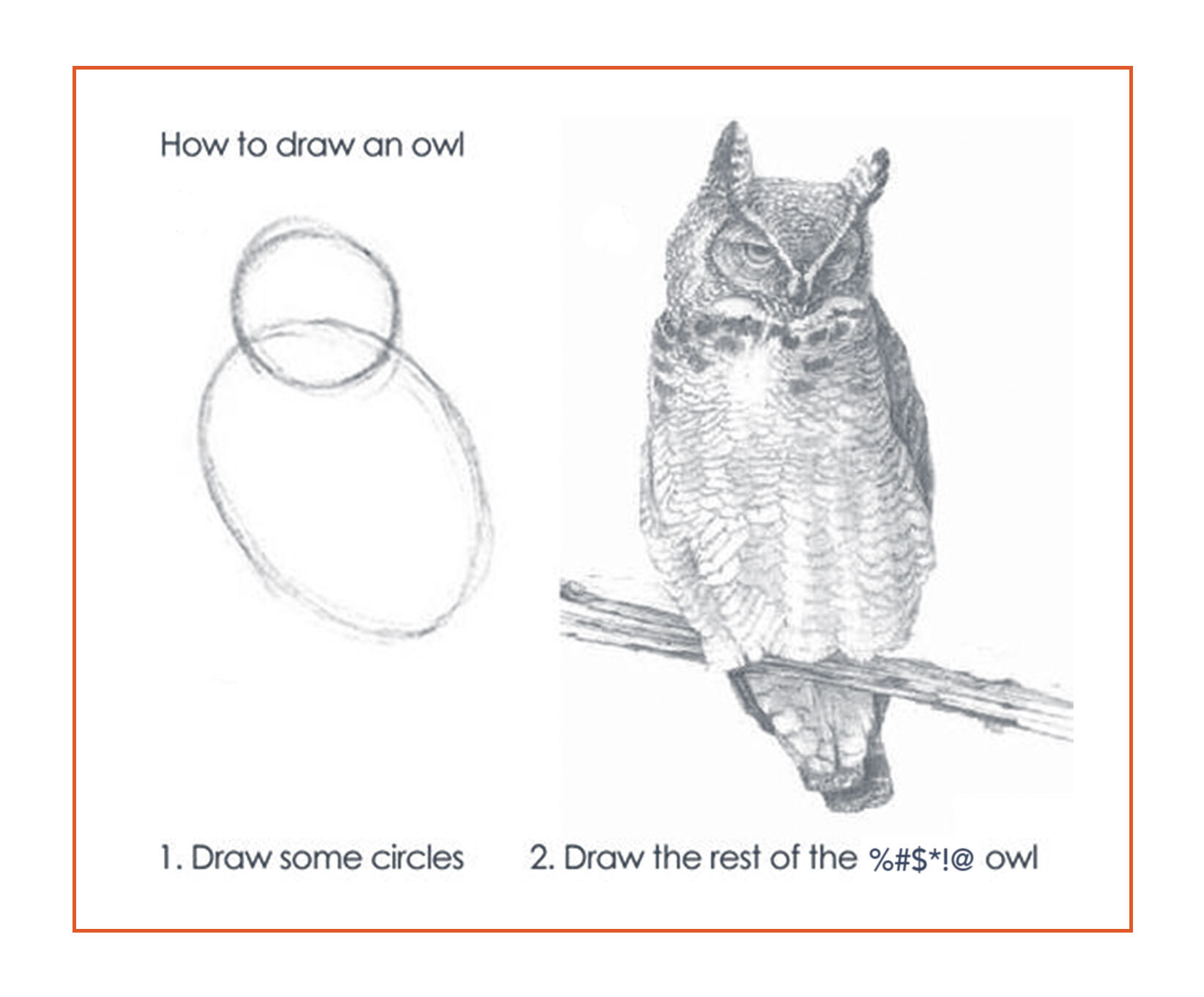

I think of decisions, not lines of code or stories or features, as the organizing principle of software. Those other things tend to hold our attention and structure our understanding of our work, yet it’s decisions that challenge us, by definition moments of contention in which the path forward is not clear. How often do you feel like you’re drawing the rest of the owl?

A Hierarchy of Engineering Decisions

Let’s create a hierarchy of decisions made by a software engineer, based on a few dimensions:

- How often the type of decision is made,

- How important the decision is to the software context, and

- How much they are documented.

Fortunately, these dimensions are all correlated. The importance of the decision should correspond to the amount of documentation it receives (though not perfectly, as we’ll see). And those are both inversely correlated to how often the decision is made.

We could visualize this like so:

In practice, engineers traverse this hierarchy throughout a project, moving up as they realize key questions are unanswered, and then back down to resume design and implementation. Let’s look at each tier.

Product and project decisions. Upstream of everything else are decisions about what will be made, for whom, and cover the entire application. They give the reader a broad sense of what will be built (think OKRs and roadmaps), but lack sufficient detail for implementation. Typically of more abstract interest to engineers.

Design and architecture. Here decisions start to take on a more concrete character, and correspond to features of the application. Designers determine what users will actually be doing in the application, mapping workflows and creating designs. This now gives engineers enough information to begin architecting the application, deciding on entities and the relationships between them.

Implementation. Documentation starts to recede in favor of the code that instantiates the application. Decision-making doesn’t stop, though – it turns inwards, and becomes an engineer-to-engineer affair. PR descriptions and reviews, classdocs, unit tests and code itself record how engineers implement the designs and architecture.

“Nits.” Finally, we step away from explicit documentation almost entirely. These are the innumerable small, often unconscious decisions that engineers make as they code: naming, preferred syntax, class responsibilities, and other considerations that usually fall under “style”.

What jumps out about this schema? Engineering decisions are proportionally much less documented. This is fine at lower levels, but if it persists into the architecture tier, it results in under-documentation of important decisions, and thus software that is hard to understand and iterate on. This is why we want ADRs – they fill in a common gap that appears in engineering documentation.

Whither ADRs?

Let’s return to our original question:

- When do software engineers write ADRs?

With our lay of the land, let’s climb back up our hierarchy and try to answer this question:

- When do decisions cohere into something meaningful?

Well, this happens during design and architecture. It’s why feature mockups are a key output of designers – they’re the point at which a group of decisions can be understood with minimal reference to other decisions. The placement of a particular input or button is not particularly significant by itself. Conversely, I don’t need to know what a website is selling to understand the meaning of a checkout experience.

Architectural components are engineering’s features: the coherently meaningful features of a codebase. One class, taken in isolation, probably doesn’t mean much (provided it isn’t a Death Star), but several classes collaborating together to create a notification queue is perfectly intelligible, regardless of what the rest of the application does.

The challenge for engineers is knowing when they’re doing architecture. We know this when we answer “yes” to the following:

- Does this decision change the fundamental meaning of the codebase? Is it essential to understanding the functioning of the application?

As I mentioned, a software team travels up and down the decision hierarchy as they do their work. Engineers typically know they’re architecting as they travel down the hierarchy, responding to decisions made by product and design teams. The real difficulty is knowing when you’ve climbed back up, from implementation into architecture. This is the feeling of “deciding the rest of the owl” – a hint to you, the engineer, that you’re making a decision worth recording.

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.